On February 25th, I headed to Parliament to attend a Senate committee meeting on the fate of Bill C-279, An Act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code (gender identity.)

This was my third time at Parliament to observe the progress of this bill through the legislative process. I was in the House of Commons when it passed Third Reading in 2013 and in the Senate last fall for hearings.

When I walked into the conference room, things weren’t looking good for the bill. It was getting dangerously close to election time. After four years of proceedings, including a 20 month delay between passing Third Reading in the House of Commons and a first look in the Senate, the election was now only a year away. Any bill that hadn’t yet become law by that time would be killed.

Meanwhile, any amendment would throw the bill back to the House of Commons. If it landed there, it was unlikely to pass in time for the election.

However, the introduction of an amendment became inevitable. During the time that Bill C-279 languished in the Senate, Bill C-13 was introduced, passed both the House of Commons and Senate and received royal assent. Bill C-13 added sex, age and disability into the hate crime provisions of the Criminal Code. Bill C-279 added gender identity. If C-279 passed without amendment, it would erase the protections C-13 had introduced. So an amendment was now necessary.

The meeting started and as it progressed the addition of two amendments was confirmed. This included the expected amendment to be compatible with C-13. The majority Conservative government had won – the bill they had opposed would all but certainly die on the floor. There was only a glimmer of hope that it could pass.

Then something else, wholly unexpected happened. The Conservatives, through the former president of the Conservative Party Senator Don Plett, introduced a third amendment that would turn Bill C-279 from legislation to prohibit discrimination into one that would support it. It added the following exception to the Human Rights Act:

15. (1) It is not a discriminatory practice if

(f.1) in the circumstances described in section 5 or 6 in respect of any service, facility, accommodation or premises that is restricted to one sex only — such as a correctional facility, crisis counselling facility, shelter for victims of abuse, washroom facility, shower facility or clothing changing room — the practice is undertaken for the purpose of protecting individuals in a vulnerable situation;

The intended effect of the amendment as judged from Don Plett’s previous comments in the Senate was to protect discrimination under law. I replaced slurs for trans women in the following quote from Senator Plett with [trans woman]:

I want you to tell me, Senator Mitchell, when you say that 0.3 per cent of society is trans, how their rights can trump the rights of my five-year-old granddaughter walking into a change room, a [trans woman] walking into a bathroom … How can this 0.3 per cent of society trump the rights of my grandchildren, my granddaughters?

And later Senator Plett added:

Mr. Dyck, you have in your testimony used a comparison of trans people not being allowed in certain areas. You’ve used a comparison of Blacks not having been able to be allowed. Mr. Garrison used the same analogy when I asked him about my five- or six-year-old granddaughter not wanting to go into the bathroom or a change room with a [trans woman]. He inferred that it was the same as my granddaughter not wanting to go into the bathroom with an Asian or a Jew. I found that tremendously offensive. I do not believe there is any comparison, when we talk about colour or race, to somebody who is biologically male or female.

The bill had gone from prohibiting bans on trans women seeking to use the women’s washrooms or men seeking to use the men’s washroom to supporting these bans. Likewise for denying abused women access to women’s shelters, sending individuals to the wrong correctional facilities, and denial of service to any gendered service, facility, accommodation or premises. Trans women were portrayed as a threat to cisgender women and children.

The vote for the contentious amendment passed, with unanimous support from Conservative senators, to the incredulity of the bill’s supporters. Members of Gender Mosaic, who had lobbied for this bill walked out. I followed.

Whatever glimmer of hope I had for this bill faded at that time. The Conservatives had opposed the bill from the get-go and the supporters would now have to oppose its newest form too:

“We still want to support the bill, because it’s important for the trans community, but if it’s going to have the amendment in it that restricts our use of washrooms and public facilities… no,” said Amanda Ryan from the advocacy group Gender Mosaic.

“It’s a bad bill with that amendment in it. We want to fight as hard as we can to have that removed,” she told CBC News Network’s Power & Politics on Thursday.

The implications of the new amendments were quickly picked up by the biggest media outlets, to my surprise. The Toronto Star reported “Trans rights bill amendment would bar trans people from public washrooms,” while Maclean’s opined “How discrimination got in the way of the federal transgender rights bill.” Even the right-wing Toronto Sun ran the story “Senate guts transgender rights bill” that took a supportive angle. Though as expected, the readership for all these publications overwhelmingly expressed vitriolic views towards trans people invoking tropes of “mental disorder”, “threat”, “special rights”, etc.

How things had changed. Just a year ago those headlines might have read “Trans rights bill amended” or something equally devoid of critical analysis. But how had an anti-discrimination bill come to support the very discrimination it had been designed to oppose?

History

Predecessors to C-279 had been introduced as private member’s bills in 2005, 2006, and 2009 by NDP MP Bill Siksay.

The first two attempts did not get off the ground, but the third had passed Third Reading only to die in the Senate when the 2011 election was called. It was reintroduced by NDP MP Randall Garrison in 2011 following Bill Siksay’s retirement.

The Original Bill

The bill as it was introduced in 2011 would amend the Human Rights Act to include gender identity and gender expression. Section 2 of the Canadian Human Rights Act would be replaced with the following:

Purpose

2. The purpose of this Act is to extend the laws in Canada to give effect, within the purview of matters coming within the legislative authority of Parliament, to the principle that all individuals should have an opportunity equal with other individuals to make for themselves the lives that they are able and wish to have and to have their needs accommodated, consistent with their duties and obligations as members of society, without being hindered in or prevented from doing so by discriminatory practices based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, marital status, family status, disability or conviction for an offence for which a pardon has been granted.

The bill would also amend the Criminal Code to include gender identity and gender expression as prohibited grounds for discrimination. Subsection 3(1) of the Act would be replaced with the following:

Prohibited grounds of discrimination

3. (1) For all purposes of this Act, the prohibited grounds of discrimination are race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, marital status, family status, disability and conviction for which a pardon has been granted.

That was it – four words repeated in two sections.

Journey Through the House of Commons

It was after its introduction in the House of Commons that the first instances of of the kind of language that Senator Plett used would surface.

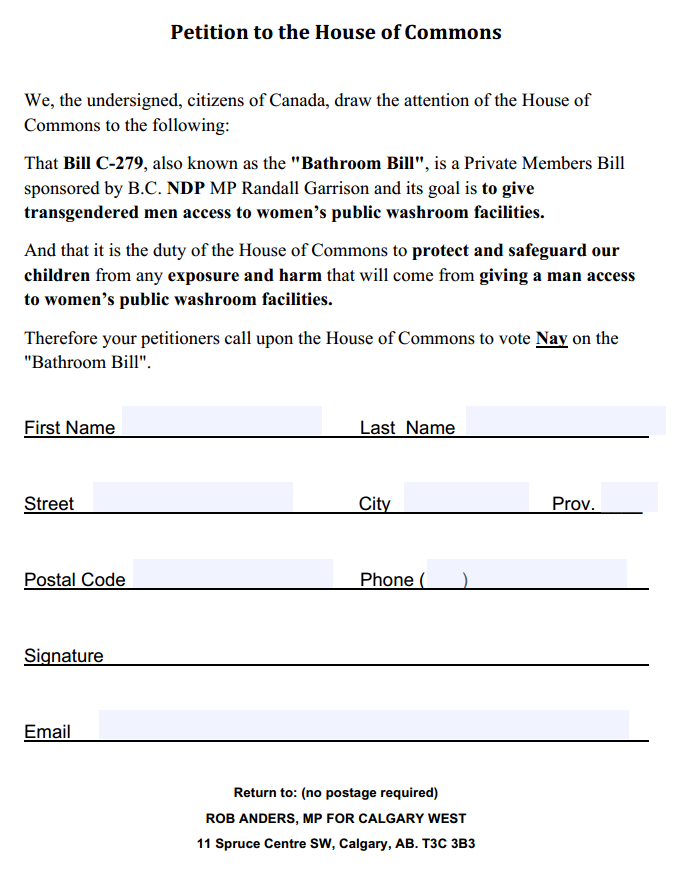

Conservative members would openly dub the bill “The Bathroom Bill” in reference to their strategy to drive support: focus on trans women and go into scare tactics about their day-to-day activities such as using washrooms. In this case, by portraying them as sexual deviants who were a threat to presumably cisgender women and children. One Conservative MP, Rob Anders, had started a petition which was available on his website in 2012:

Other Conservative MPs would use a slightly different approach where it was alleged that trans women were indistinguishable from sexual predators. As MP Dean Allison stated in the House of Commons:

I find this potentially legitimized access for [trans girl] in girls’ bathrooms to be very disconcerting. As sexual predators are statistically almost always men, imagine the trauma that a young girl would face, going into a washroom or a change room at a public pool and finding a [trans girl] there. It is unconscionable for any legislator, purposefully or just neglectfully, to place her in such a compromising position.

Conservative MP David Anderson wondered:

The first question to the member opposite is this: does he actually believe that there is no one who will try to abuse the situation that would be created by his deliberately vague legislative agenda?

The fear mongering around washrooms was rooted in prejudice but was also a distraction from talking about the real reasons behind this bill’s introduction. There was denied access to education, work, medical care and government recognition of identity. Safety in public venues was a big issue. The environment in Canada was so hostile that 77% of trans Ontarians had “seriously considered suicide” and 43% had attempted suicide. As for washrooms, 57% of trans Ontarians avoided public washrooms “because of a fear of being harassed, being read as trans, or being outed.” Provinces in Canada and the federal government were still requiring trans people to undergo forced sterilizations, a practice condemned by the World Health Organization. Unemployment for trans people in Ontario was at 20%, double what it was for cisgender people. Conservatives did not wish to discuss any of that, or address any of that, it was about appealing to the bigots.

The Conservatives would also key in on protections on the basis of gender expression, the lack of definition for gender identity, and opposition to expanding existing laws. Conservative MP Robert Goguen wondered out loud:

If this ground were to be added to the Canadian Human Rights Act, what sorts of new complaints of discrimination will be brought before the Canadian Human Rights Commission and Tribunal? How will employers know what kinds of workplace behaviour and expression would be prohibited? The answers to these questions are not clear to me and they are questions that we should carefully consider.

In an effort to get Conservative support, gender expression was taken out and a definition for gender identity was introduced. Those two were big blows for the usefulness of the bill. Removing gender expression eliminated protections for a whole swath of people who ran afoul of gender norms or did not identify with a binary gender identity. They would not necessarily be covered under a gender identity clause.

Meanwhile a definition for gender identity was being required where none had existed for other categories such as race and disability. This would have the intended effect of further constricting the applicability of the law. The bill had been eviscerated but gender identity remained, and given the violence faced by trans people throughout Canada, I thought it could be better than no law at all.

With modifications the bill passed but just barely with 149 votes in favour and 137 against. Unsurprisingly, the opposition came entirely and only from the Conservatives: 136 of those 137 votes against were from the Conservative Party, with the remaining opponent being a former (and soon to be reinstated) Conservative party member. The other parties were all unanimous in their support. The tiny fraction of Conservatives who voted in favour of the bill (12%) was just enough to make the bill pass.

By this point it was only two years after the 2011 election. There was plenty of time left to pass through the Senate and become law. I was optimistic.

The Senate

The bill would languish for a year and a half in the Senate with no action. Finally, there were hearings in October 2014. I documented my experiences on this blog.

Conservatives would again focus on making the case for persecuting trans women. During one of the hearings, Senator Plett read a letter out loud:

For this last one, I will read a letter — and I have received many — before I ask my question:

Dear Mr. Plett,

As a father and a care-giver for children, as well as my 84-year-old mother with dementia, I thank you for fighting to keep washrooms a place where we do not fear the awkwardness of sharing with the opposite gender.

It goes on to say:

My wife grimaces at the thought of trying to help our handicapped daughter or our mother in anything but a female-only washroom.

May God grant you wisdom.

It is signed ”Carl.”

Now he is not suggesting that his wife is afraid of people. There’s an awkwardness. I’m not suggesting my granddaughter is afraid of these people. There’s an awkwardness.

Do you not believe, Mr. Dyck, that these people also have the right to their own privacy at all costs? Apparently 0.3 per cent of the people in our country are trans. Are we not infringing and trumping somebody else’s rights by giving trans people the right to go into these areas?

It was a continuation of this distraction to avoid talking about the discrimination that people faced because of their gender identity. The Conservatives were in the territory now of alleging that not discriminating against this group of people would itself constitute an infringement of rights.

It was with this history then that this amendment was introduced. As Senator Plett stated in his speech accompanying the amendment:

This amendment will protect those operating sex-specific facilities in federal jurisdiction for example, bathrooms, military base change rooms and shower rooms, and women’s shelters on first nations reserves if they decide not to allow for example a [trans woman] self-identifying as female into a sex-specific facility for the purpose of protecting vulnerable women.

By putting in an exception in which a person discriminated against on the basis of their gender identity would explicitly be denied a legal recourse because the discrimination was gender related made the bill not just useless but actively harmful. Living in a country absent of an anti-discrimination law would be better than living in one where the law explicitly permitted and supported discrimination.

The Future

The bill will now be debated in the Senate and sent back to the House of Commons. If the bill passes as-is, discrimination will be legalized.

Realistically, the passage of the bill in its original form would not have had an immediate impact on the day-to-day activities of those who live with the effects of discrimination. Most obstacles, such as health care and education, exist at the provincial level. For Ontarians, Toby’s Law passed in 2012, brought the changes originally proposed by Bill C-279 including gender expression into provincial legislation. With the passage of something like C-279 on the federal level, I’d imagine you would have seen cases to address the current passport requirements from mandating compulsory sterilization and two genders to something like Australia’s system, which only requires a letter from a doctor and offers a genderless option. It might also have helped bring in new policies for the correctional system as well as make government-funded services accessible, etc. Those would have been legal cases years down the road.

The hate crime provisions, meanwhile, would not have contributed to a better environment. It would have done nothing towards addressing the discriminatory policies embedded in institutions. Arguably the bulk of the discrimination faced by people. Nor would it have prevented the perpetrators of assault from engaging in these attacks as assault is already illegal. It would have meant that police forces would have recorded instances of transphobic violence that were reported.

Laws don’t do much to address all the tiny manifestations of discrimination or their staggering cumulative impact. When opportunities are systemically denied due to discrimination, then it’s not just laws like what C-279 proposed that come into play, but Canada’s repressive laws against sex workers and toxic attitudes towards the poor or those without post-secondary education. It’s also the hierarchies of administrators and policy makers unwilling to introduce change that would address obstacles disproportionately experienced by trans people. Bill C-279 was never going to fix all those things but act more as a symbol for where we want to be.

Given the supportive reaction to this bill’s outcome, however, a future where violence against non-cis people isn’t regarded as normal might not be as out of reach as I once imagined.