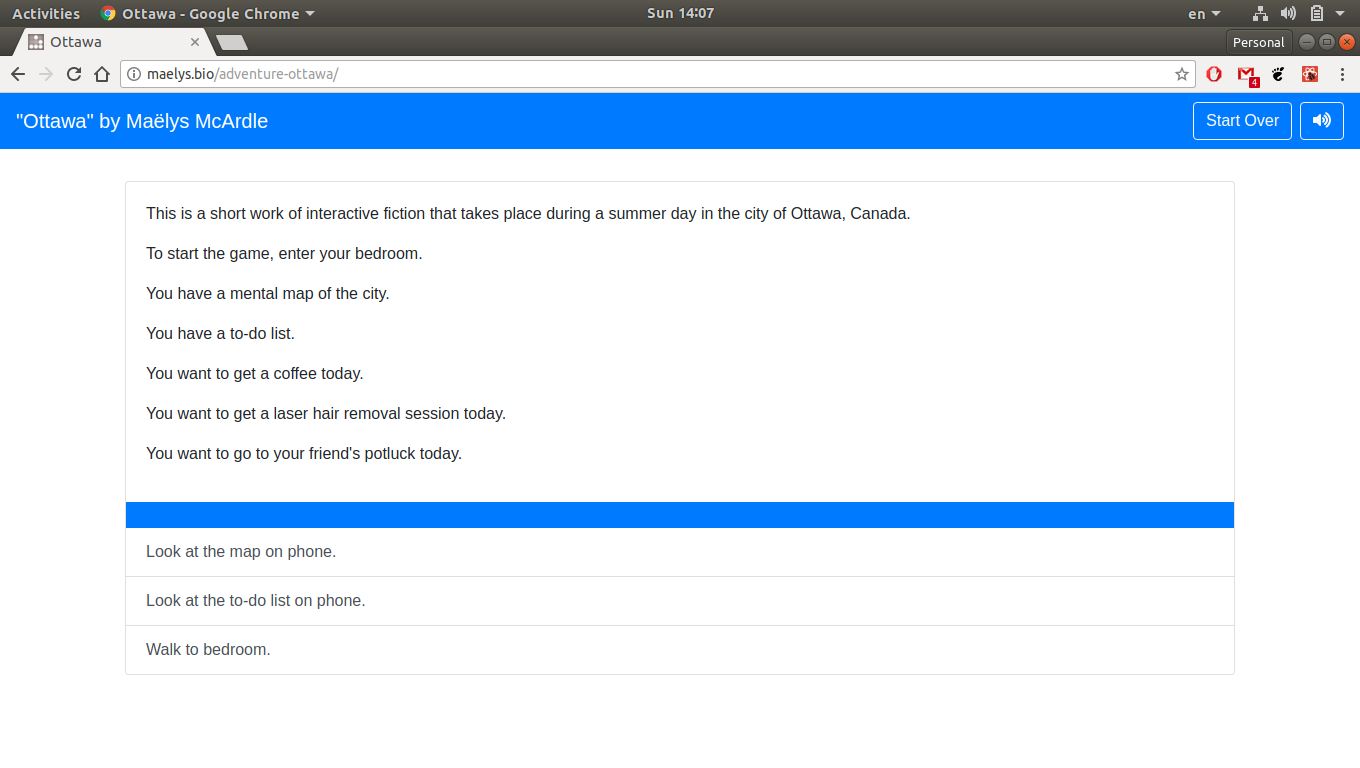

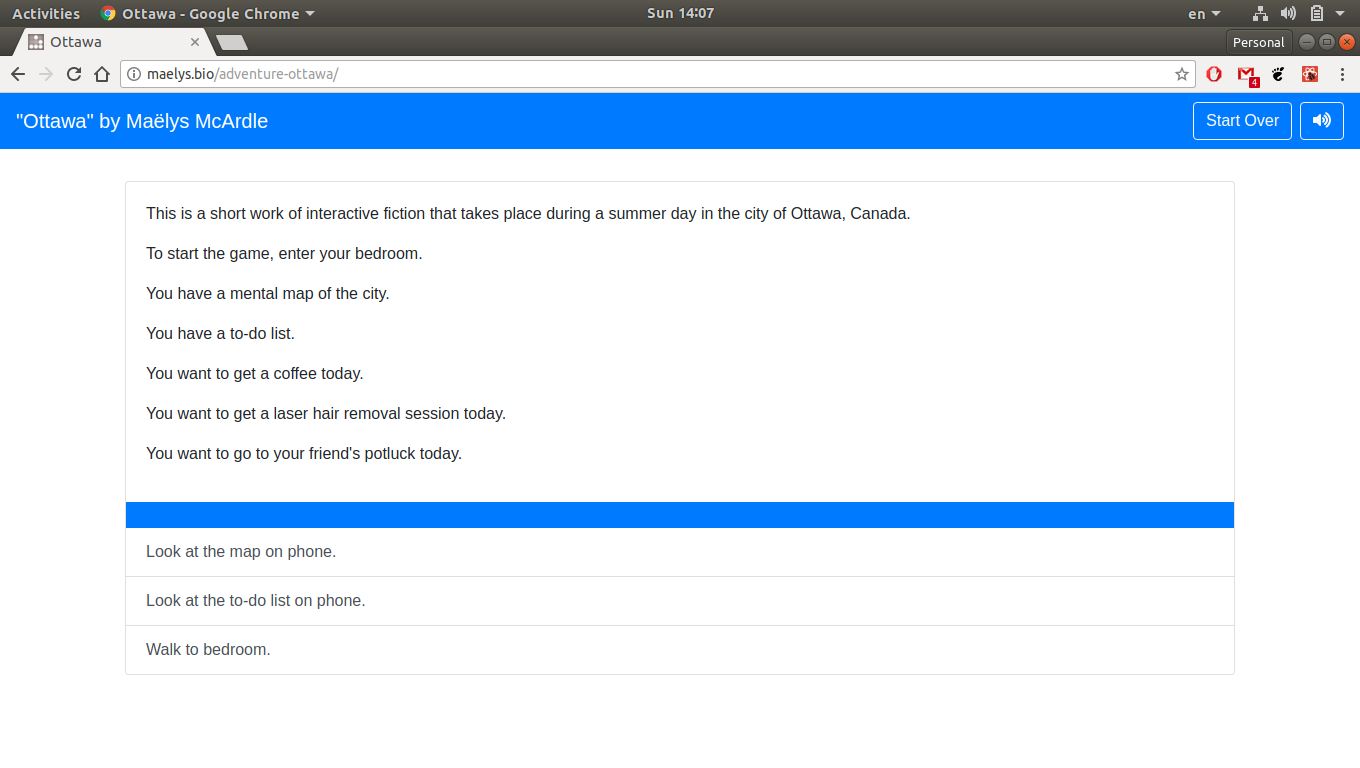

Today I’m proud to show off a short work of interactive fiction that I wrote, about being trans in Ottawa. You can play through the story by clicking here.

In the rest of this post, I’ll talk a bit about the process behind the creation of this game.

Four Stages

From the outset, I realized that I wanted to create my own interactive fiction engine, that is to say, my own tools to create works interactive fiction. I did this because I thought it would be quicker to write my own than learning to become proficient in someone else’s, and because I had the ultimate goal of making the works I produced available online. I thought it would be easier to accomplish the latter if I didn’t have to work with someone else’s tools.

This would be the second interactive fiction engine I created. I used lessons I learned from my first go at it, Story Creator. Story Creator was designed to be easy to learn, but wasn’t scalable – writing longer and more complex stories became unmanageable.

If I wanted to create this work, I needed to follow four steps:

- Design a scripting language with which to create stories.

- Put together an interactive fiction engine that could turn those stories into playable games.

- Create a tool that would use the interactive fiction engine, and create a website through which people could play the game.

- Write the work of interactive fiction I had intended.

Creating the Scripting Language

I set out to create a scripting language – a way to formulate stories that a computer could understand as to make playable experiences. I spent a week or two writing tidbits of code on paper, imagining how a story could be written. This was a really fun challenge for me.

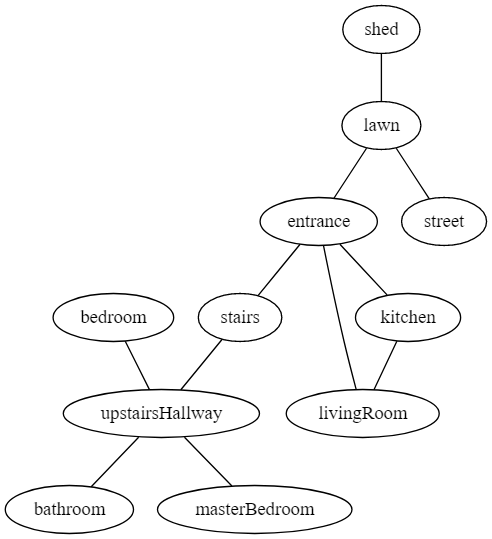

I realised that these stories, much like computer programs, could be boiled down into two fundamental ingredients: state machines and the means to move between them.

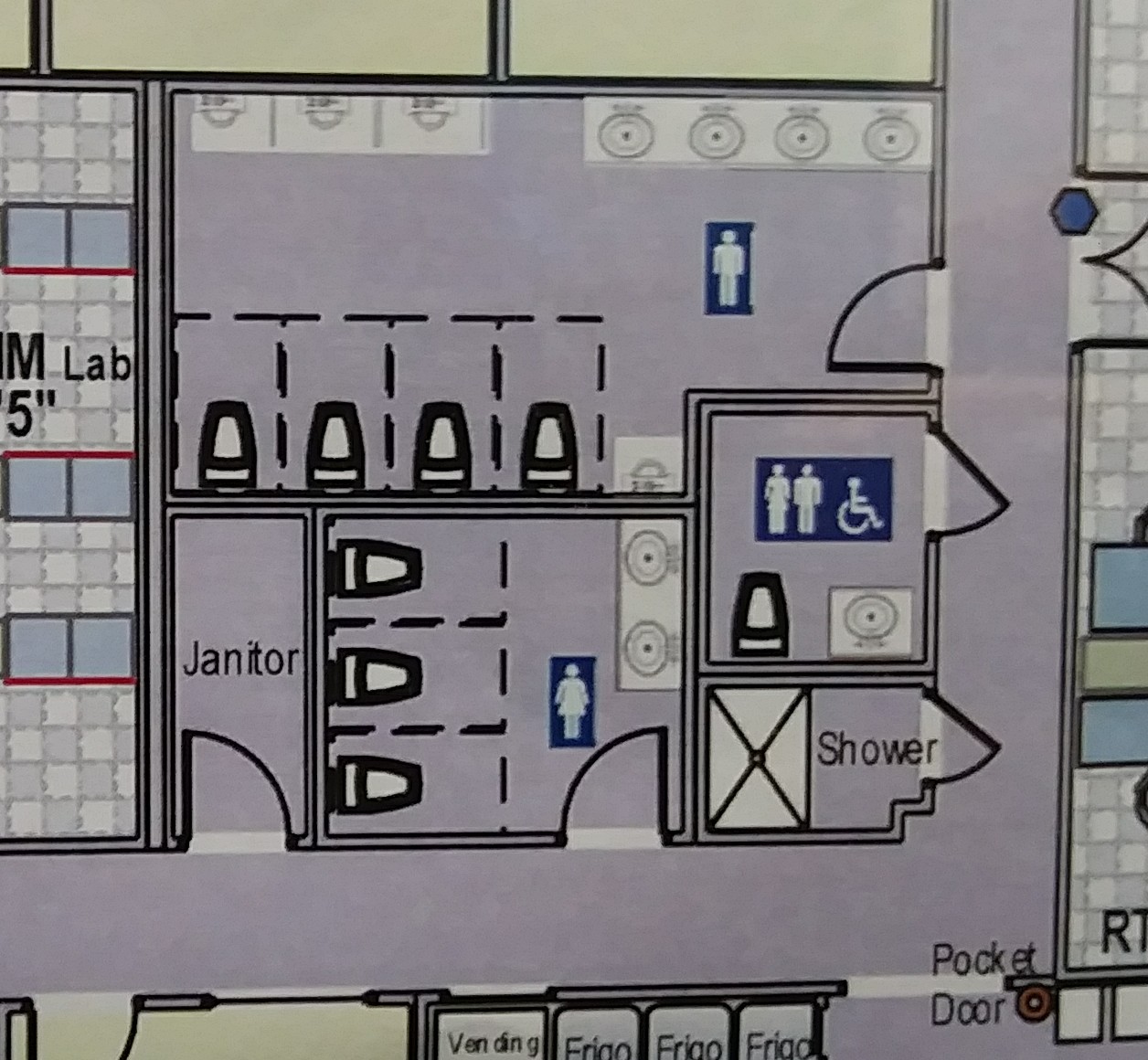

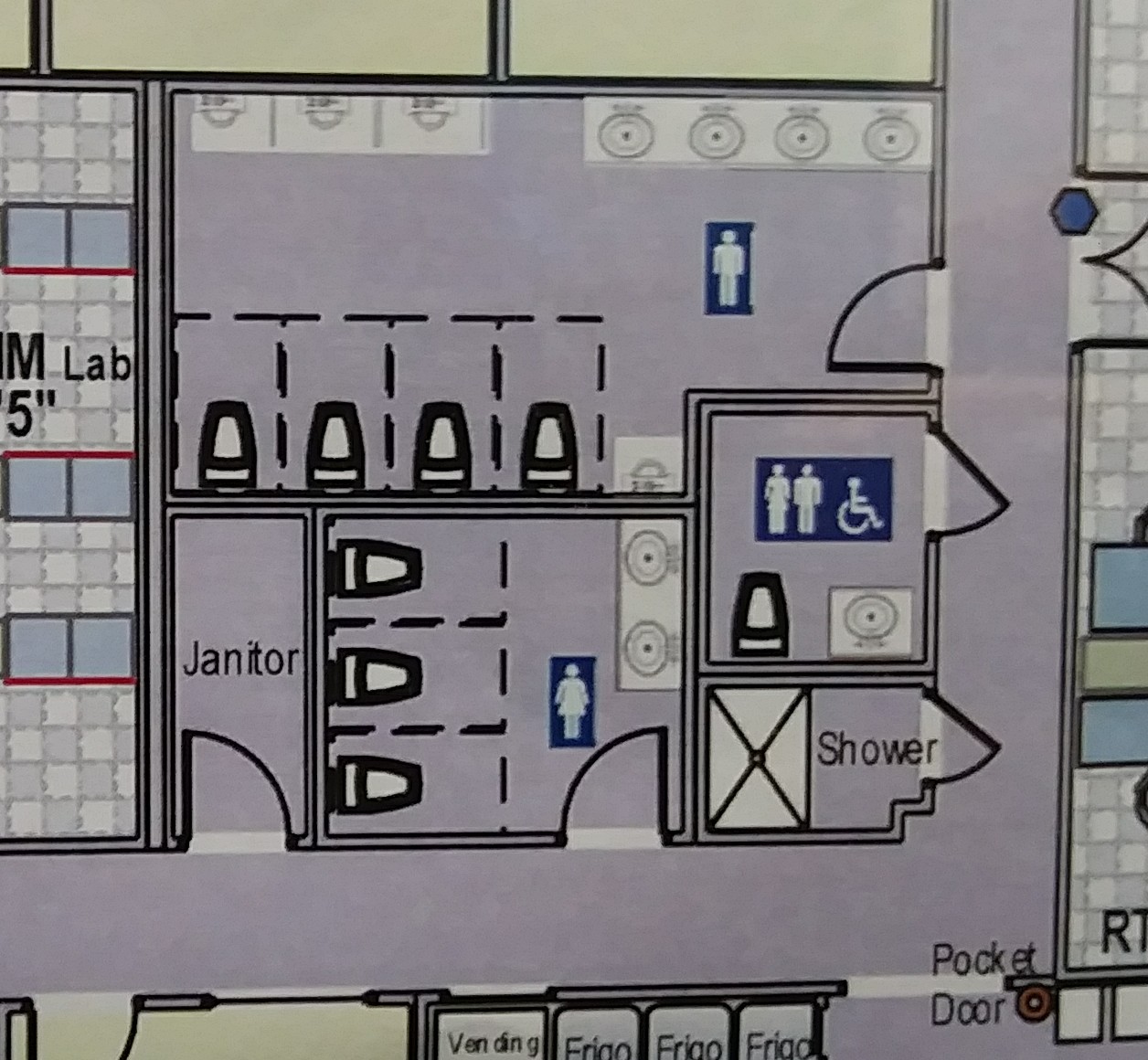

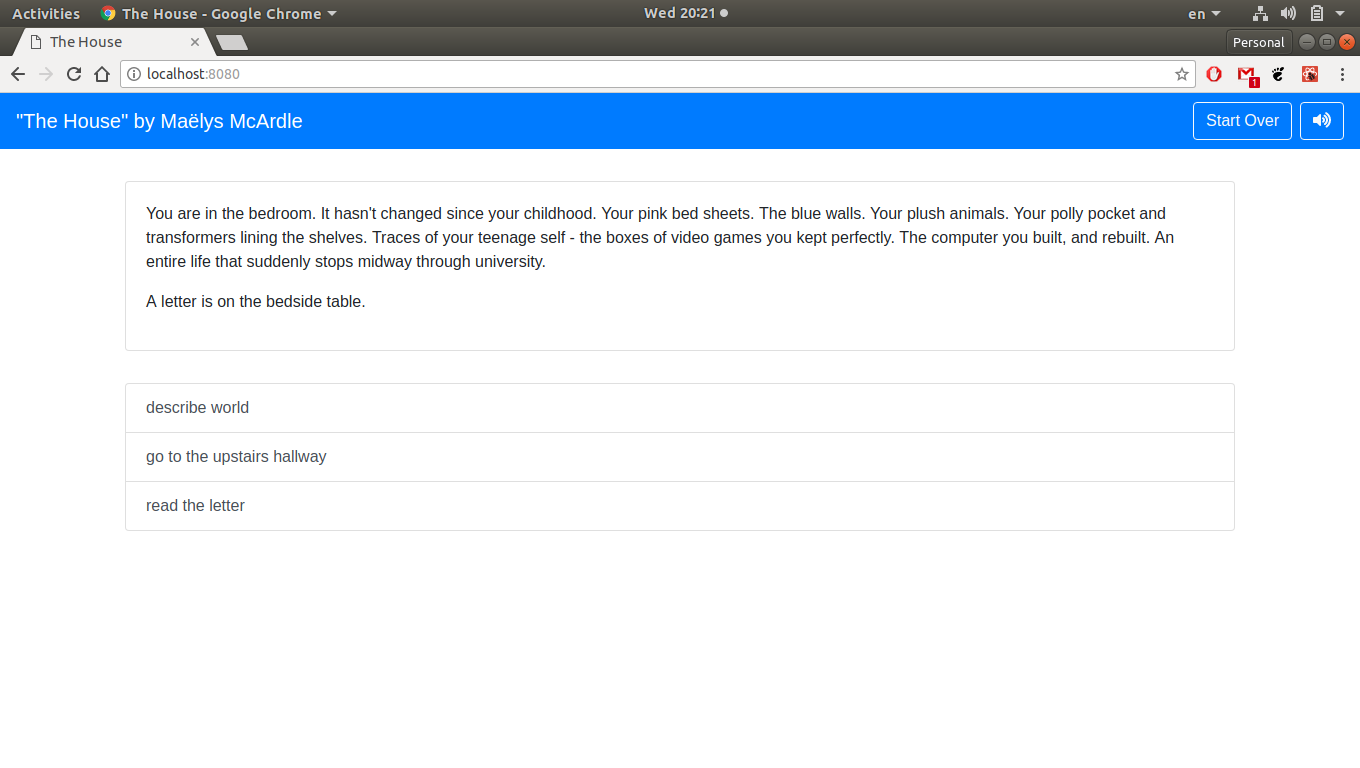

Everything in a story can be reduced to a state. The location of a player (bottom left) or a conversation with a character in the story (bottom right).

In the case of a work of interactive fiction, each state can have text associated with it. If the player is in a bedroom, then there can be text specific to that, talking about the bed and so forth. If the player is in a different location, say, a washroom, the text can be different, talking about the sink and tub.

The other fundamental ingredient, actions, change the state of these state machines. These actions can have different names depending on the state machine. For changing the location, the action could be called walking. For navigating a conversation tree it could be called speaking. The name is irrelevant. They all do the same thing: change state machines from one value to another.

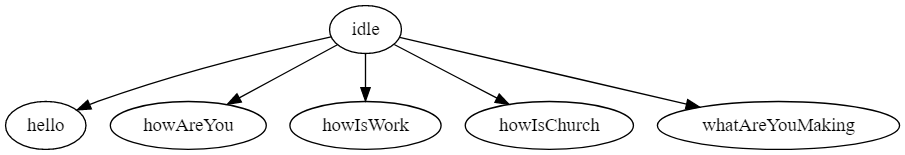

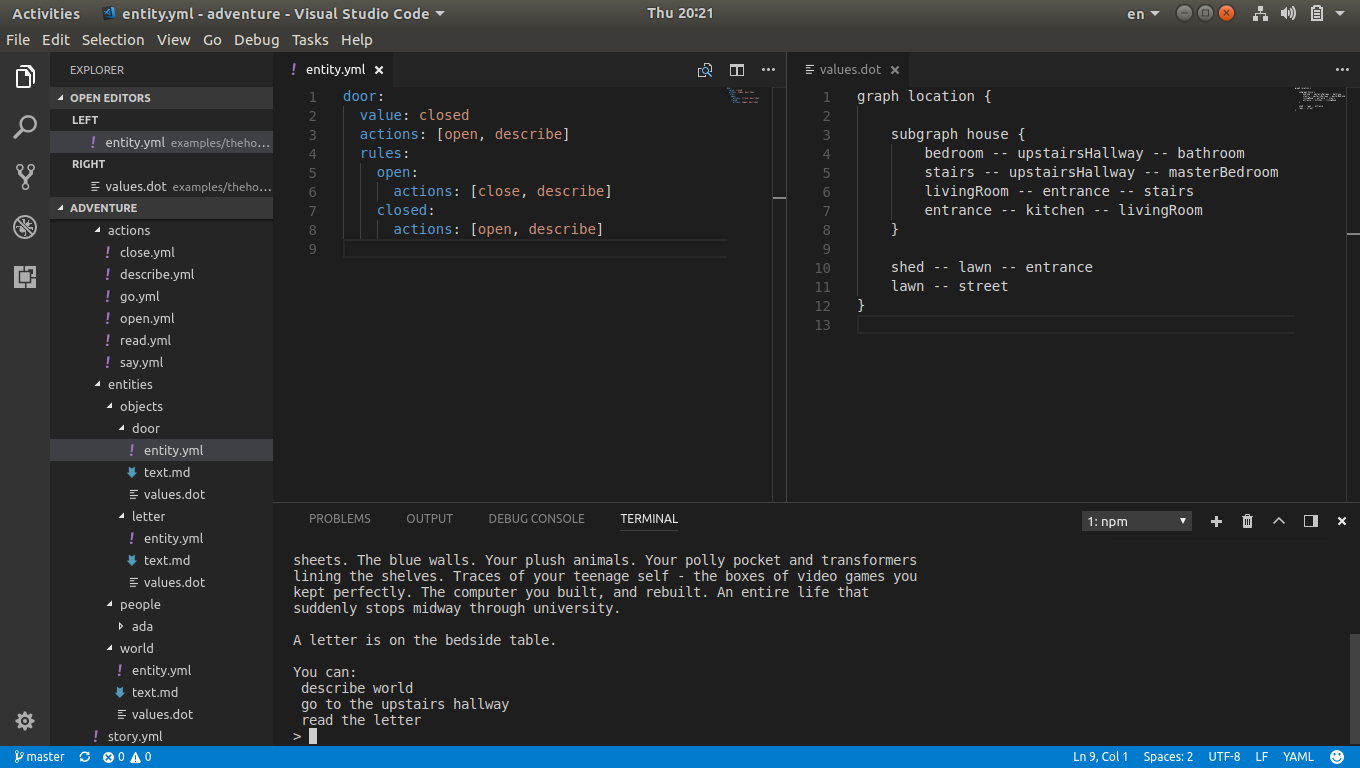

With that in mind, I separated the scripting of these stories into two: entities which would contain the state machines, and actions to change their state. The state machines would be defined using a graph description language called dot.

In them, only the states of a state machine would be defined and how the states went from one to another.

graph location {

subgraph house {

bedroom -- upstairsHallway -- bathroom

stairs -- upstairsHallway -- masterBedroom

livingRoom -- entrance -- stairs

entrance -- kitchen -- livingRoom

}

shed -- lawn -- entrance

lawn -- street

}

For the text to display with each state, I used a lightweight markup language called Markdown.

# location ## house ### bedroom You are in the bedroom. It hasn't changed since your childhood. Your pink bed sheets. The blue walls. Your plush animals. Your polly pocket and transformers lining the shelves. Traces of your teenage self - the boxes of video games you kept perfectly. The computer you built, and rebuilt. An entire life that suddenly stops midway through university. ### bathroom You are in the bathroom. ### entrance You are at the entrance.

Then for anything else related to the state machine, such as what initial state the state machine should be in, and what actions apply to the state machine, YAML was used.

location: value: bedroom actions: [walk]

Actions were also written in YAML. The idea was to trigger a change in state, to a specified value, by pattern matching against the sentences written by a player.

action: change

templates:

- walk to the @value

- walk to @value

- walk the @value

- walk @value

synonyms:

walk:

- travel

- go

- head

- enter

The scripting language I designed on paper only received minor alterations during the implementation.

Writing the Engine

Writing the engine took place over the course of many months; I wrote about my efforts here when I was done. The task was broken into four parts:

- The first was creating a compiler which would take works of interactive fiction written in the scripting language defined earlier and turn it into state machines it could use.

- The second part was creating an engine which took the state machines and changed their state according to what the player wrote to advance the story.

- The third was creating a command-line tool that could act as a front-end for the compiler and engine.

- The fourth was documenting everything including how to write stories and all the parts of the engine. There’s no way I’d remember all the details in six months.

In reality, all parts took place more or less simultaneously. I put together short works of interactive fiction, which I would pass through the compiler/engine using the command-line tool to test.

I was very pleased with the end result. You could write simple sentences, and the engine would understand it, or present alternatives that it thought it understood.

Writing the Web Tool

Command-lines like that above were very convenient to me, as a software developer who enjoys retro experiences, but inaccessible to most people. If I wanted to create something other people could experience, I needed to put it online, and I needed to remove the part where people could write sentences in plain English. I created a tool that made websites for the interactive fiction, so that the only thing someone needed to play them was a web browser.

This portion only took a week to do. The majority of the work had already been done when I created the engine. Meanwhile creating simple dynamic websites was easy with React, Bootstrap and Gulp. I wrote the code to combine the two.

Creating the Interactive Fiction

With tools in hand, I set out to create the work of interactive fiction. I had wanted to do a story about being trans in Ottawa. I wanted to show how transphobia was embedded in the everyday – whether walking down a sidewalk, going into a shop, reading a newspaper or using the washroom. I also wanted to show other aspects, including queer spaces and friendships.

The story I ended up doing was about a life in a day in Ottawa. The protagonist starts off in their apartment bedroom, and is able to explore the city. Main Ottawa streets like Bank, Somerset, Wellington, Rideau, King Edward, etc. are here. So too are places like the Byward Market, shopping center, etc. The player is tasked with three objectives: get a coffee, go for a laser hair removal session, and attend a potluck.

I’m very pleased with the final product. Though most of the content will go unread by a casual player, there are many random events, four characters that can be conversed with, and perhaps a slightly different view of the city.

Feel free to give it a go yourself! The playable story is found here.

The code for the story, in the scripting language I created, is found here.